August 21, 2024 at 2:17 AM EDT

By John Authers

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator at the Financial Times, he is author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets.”

Save

To get John Authers’ newsletter delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here.

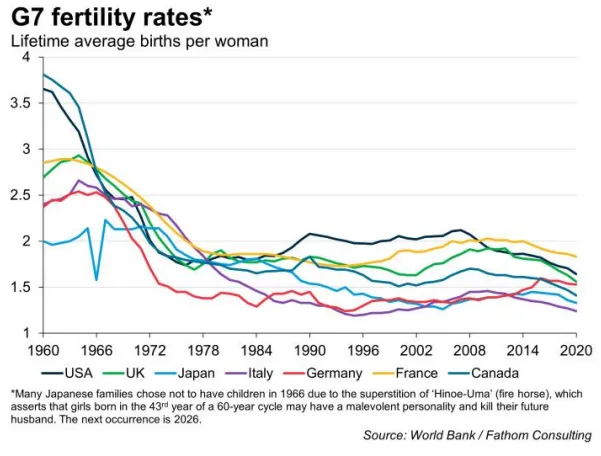

Fertility is a painful and emotive topic. Republican vice-presidential candidate JD Vance’s criticisms of “childless cat ladies” have landed him in political hot water; some 30 years ago, the British novelist P.D. James penned a terrifying novel, later followed by a film, The Children of Men, imagining a society 25 years after the last child had been born. Lack of fertility comes to mean lack of a future. Thus the economic and financial communities are researching fertility rates, with growing urgency. They’re falling in wealthier nations — startlingly fast. Fathom Consulting offers this chart of G-7 economies since 1960:

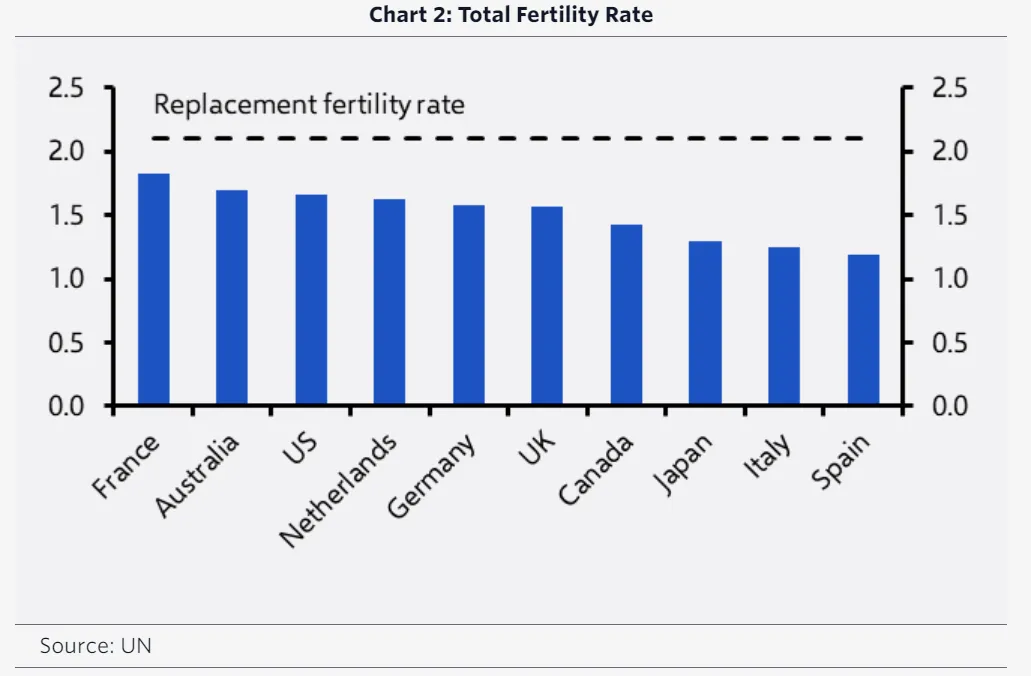

This means that populations will decline. Capital Economics shows that it’s severe across major Western countries, which have been among the world’s wealthiest countries the longest. (Note that the population replacement rate is 2.1 children per woman.)

Two hundred years ago, the presiding concern, following Thomas Malthus, was that human populations would outgrow natural resources. That was still a popular notion even 50 years ago, as any number of booksand films from the era will attest. Now, the implications of fewer people seem more alarming. Erik Britton of Fathom sets out the problems:

A declining population puts increasing pressure on already stretched public finances in the long run, and creates other stresses too as the elderly dependency ratio increases. And it also damages GDP growth (not necessarily per capita, but in aggregate). Had the fertility rate remained at 2% in the UK from 1990 to date, then the level of UK GDP would now be perhaps 15% to 20% higher than it is.

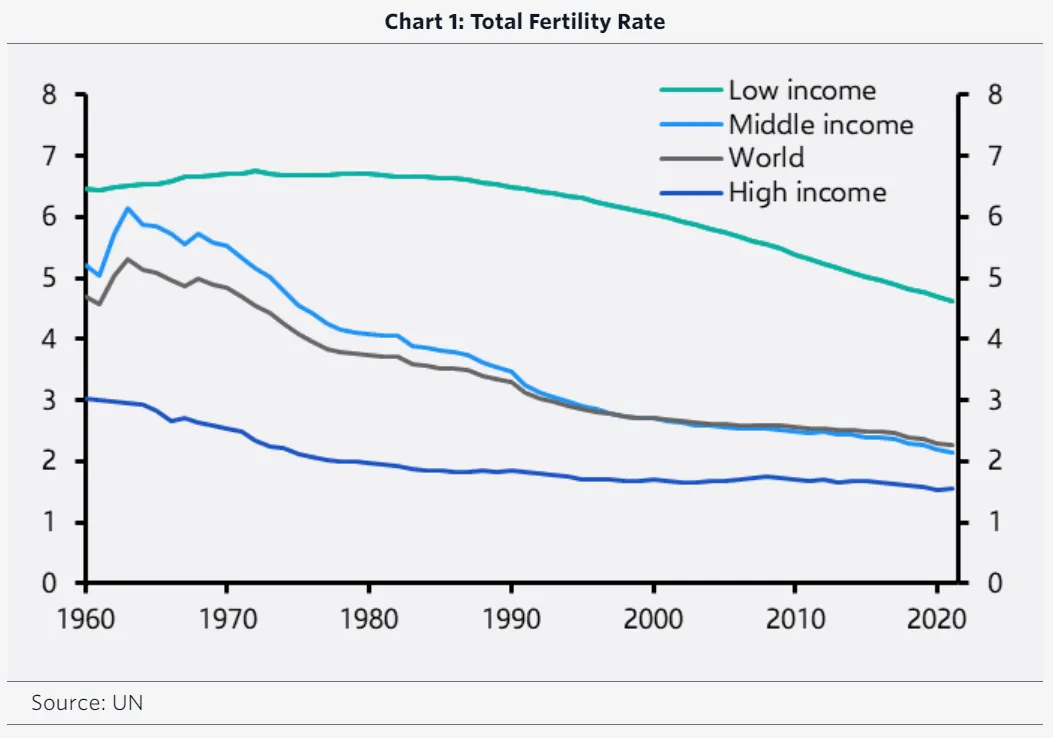

This is a problem of the wealthy. Capital Economics shows, using United Nations data, that fertility in low-income countries is roughly treble that of the richest:

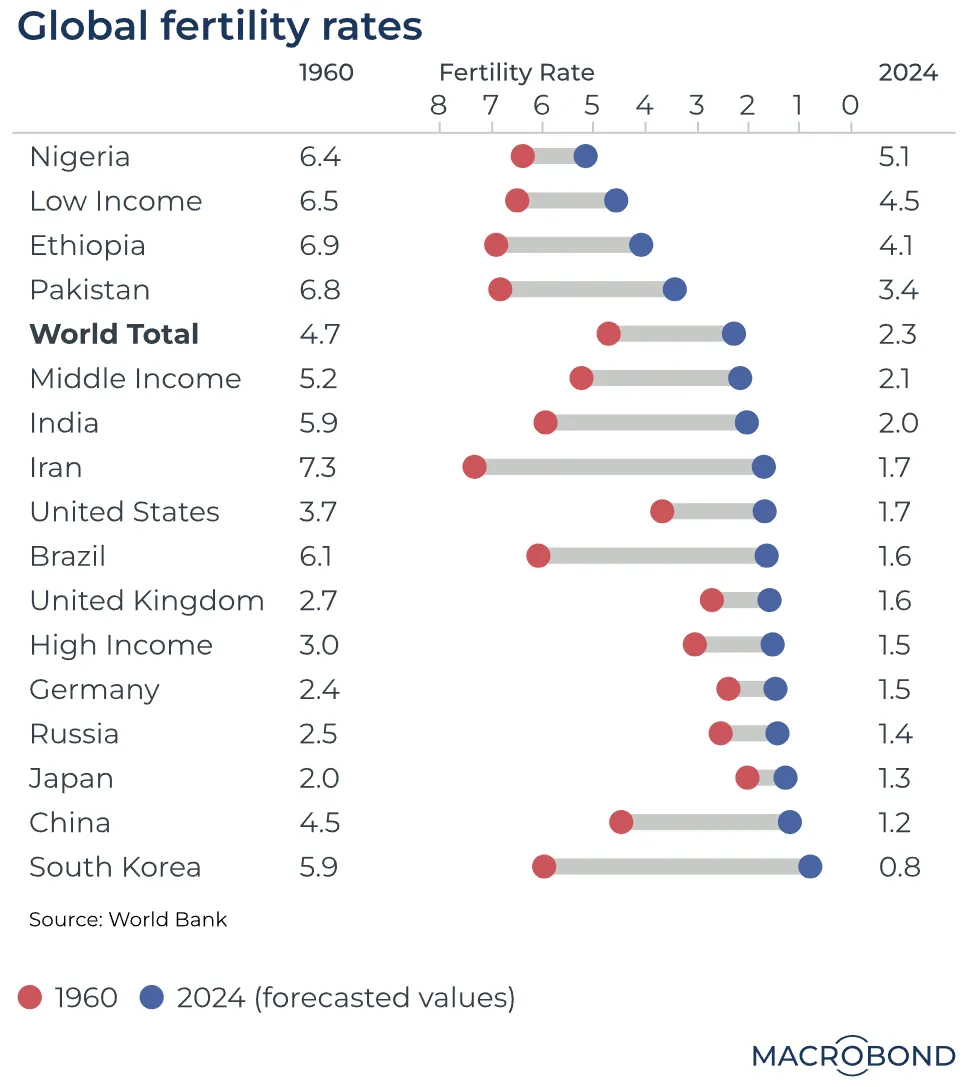

That could shift the global order over the next generation. China, which instituted a one-child policy in 1980 and maintained it for 36 years, will shrink outright as, very much more dramatically, will South Korea. This chart produced by Macrobond from World Bank data breaks down the moves in fertility rates:

This chart, from World Population Review, is ranked by projected populations of 2050, and shows the 20 most populous countries at that point. While India and China still dominate, the rankings are very different from 1980, or 2024, with a much greater weighting to sub-Saharan Africa:

Where the People Will Be in 2050

Some countries will shrink; many more will growhttps://www.bloomberg.com/toaster/v2/charts/37c7b46cc475bb7c906b846e82f8fb95.html?brand=view&webTheme=view&web=true&hideTitles=true

Source: WorldPopulationReview.com

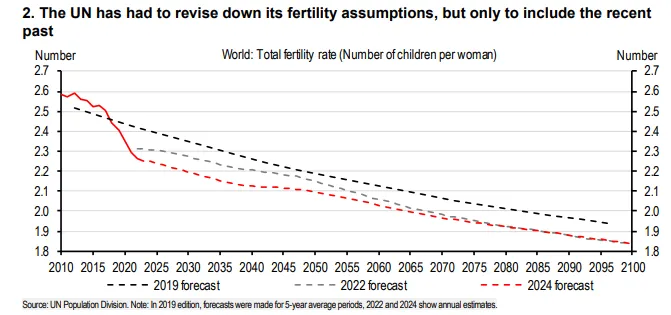

How clear can we about that future? James Pomeroy, global economist at HSBC, argues that UN forecasts may overstate populations by understating the chance that the fall in fertility continues:

We see many socioeconomic reasons to suggest that this trend may persist: increased costs of housing and childcare, shifting social attitudes towards having kids and dropping birth rates in the emerging world due to improving economic conditions and urbanization.

Might fertility rates be affected by economic gloom? Britton of Fathom Consulting explored the possibilitythat economic forecasts could factor into decisions on childbearing, not the other way around, and found a small but statistically significant relationship. He offers this worked example for the UK:

If Keir Starmer… could persuade the British public that they were going to increase that growth rate to, say, 2% (roughly where it was until the end of the 1990s) for the coming 15 years, then they would be doubly rewarded, since the British fertility rate would also increase from 1.56 to 1.85.

The investment implications are harder to sift through. Sub-Saharan Africa might come to attract more capital as it grows. In the developed world, the problem is aging; here, Bloomberg Opinion colleague Daniel Moss looks at Singapore. Veteran investor Christopher Smart writes in his Leading Thoughts newsletter:

The initial financial impact sounds largely inflationary as a large elderly population spends its savings, demands more health care services and bids up wages to fill jobs with fewer available young people. Over time… a declining population likely means sharply falling demand and greater risks of deflation.

There are many reasons that people might choose not to have large families. Such decisions open up the opportunity for profound change. With declining quantity of life, governments (and companies) would have to focus on quality.

Investment implications seem trivial by comparison, but they also demand to be confronted.