John Authers Bloomberg

Falling fertility is a problem across the developed world. Unlike many other risks, demographic changes can be predicted with some certainty; sliding birth rates translate directly into smaller populations ahead. That is a good thing in many ways. Two hundred years ago, the Malthusian fear was of population growth so rapid that it outstripped natural resources. But there are other ways in which it’s a serious problem, which could also create opportunities for those who offer solutions. And so the McKinsey Global Institute offers a new report on “confronting the consequences of a new demographic reality.” As it sounds, it’s not cheerful reading, but it shouldn’t be avoided.

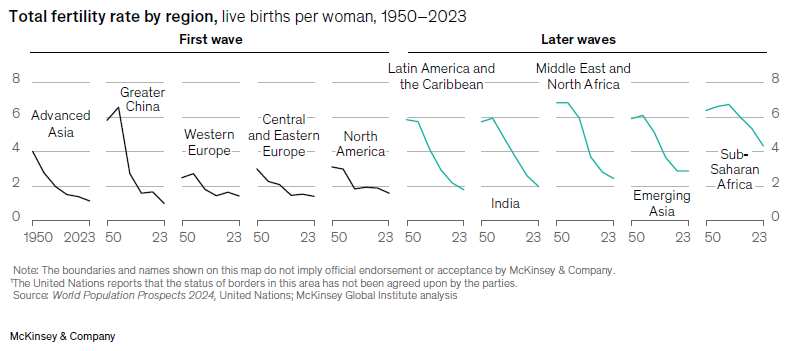

The fall in birth rates to date is universal, but far sharper in the developed world and Greater China. These countries make up what McKinsey calls the “first wave” of depopulation:

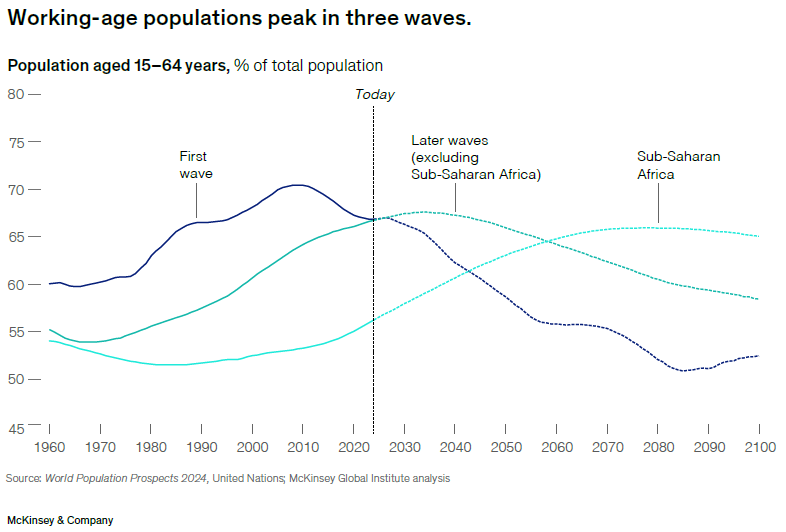

More than two live births per woman are needed to sustain populations, so declining numbers are already more or less guaranteed for much of the developed world. Lower populations will mean a smaller economy, but do not necessarily entail lower gross domestic product per capita. Problems arise as the smaller cohort of people arrives at working age. This chart from McKinsey shows those of working age (between 15 and 64) as a proportion of the total. The lower this drops, the fewer workers there are to support children and the elderly. In the “first wave” developed nations, this number peaked more than a decade ago, and is now on a serious decline. In sub-Saharan Africa, workers should keep increasing as a proportion of the population for another 50 years:

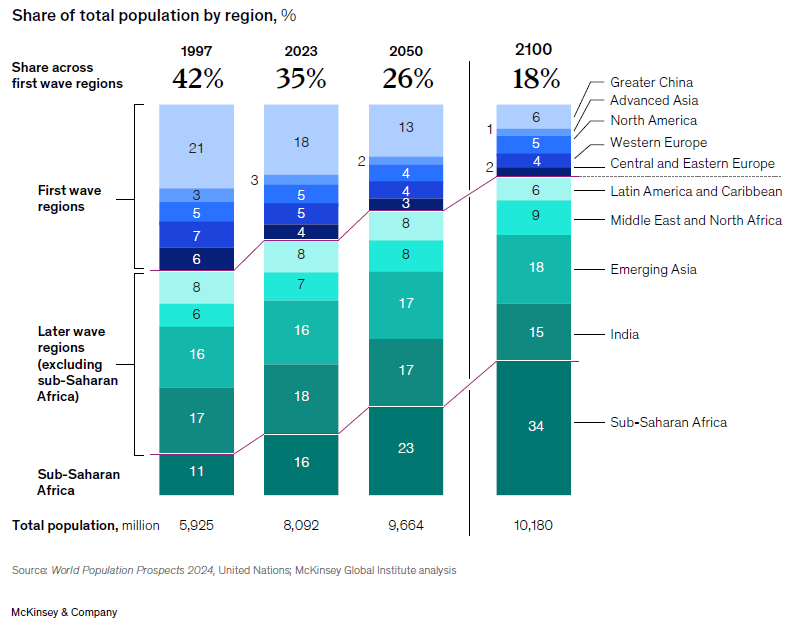

The chances are that the rest of this century will see some shift in economic power toward the Global South, and specifically sub-Saharan Africa. At present, the region accounts for 16% of the world’s population. By the end of this century, it will have risen to 34% — almost double the population of China and the current developed world:

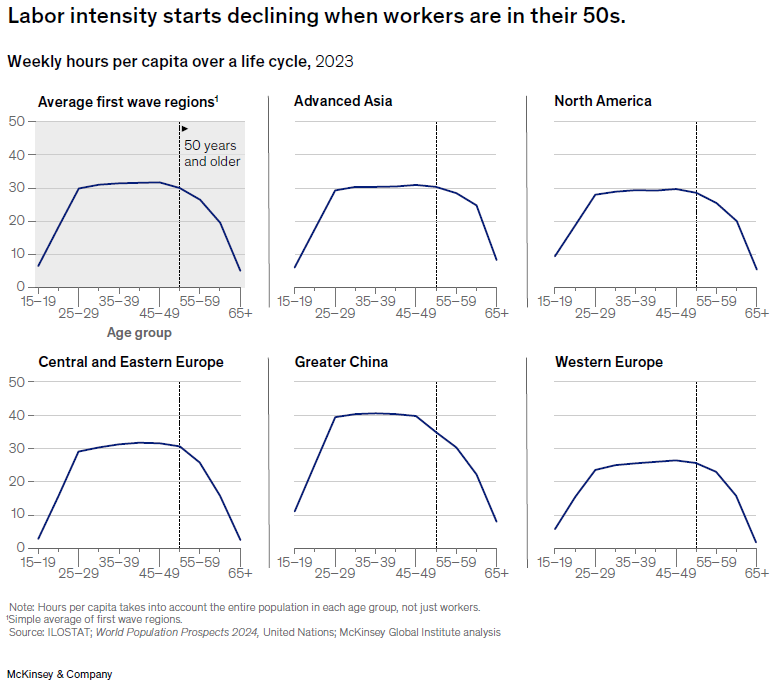

How is the developed world going to deal with this? One obvious solution is for people to work more, both through longer hours and through waiting longer before retiring. Outside of China, where people work far longer hours per capita than in the west, that is doable. McKinsey’s numbers, from the International Labor Organization, confirm that people in Western Europe at present work significantly fewer hours than in North America or the developed nations of Asia. That is in many ways a policy choice; people are glad to eschew some economic growth in return for more opportunities to enjoy life. But that deal will grow harder to sustain:

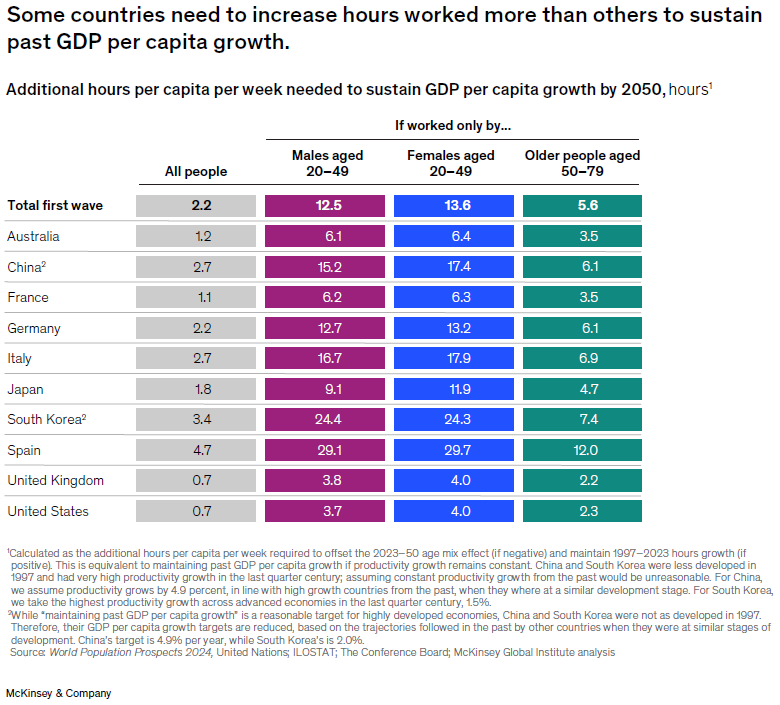

However, working longer hours on its own cannot realistically deal with the issue. McKinsey did the math. This chart shows how many extra hours different groups of the population would need to work to sustain economic growth per capita at the rate to which people have become accustomed. South Koreans under 50 would have to work 24 more hours each week. For Spaniards, this number approaches 30 hours. This, surely, is not going to happen:

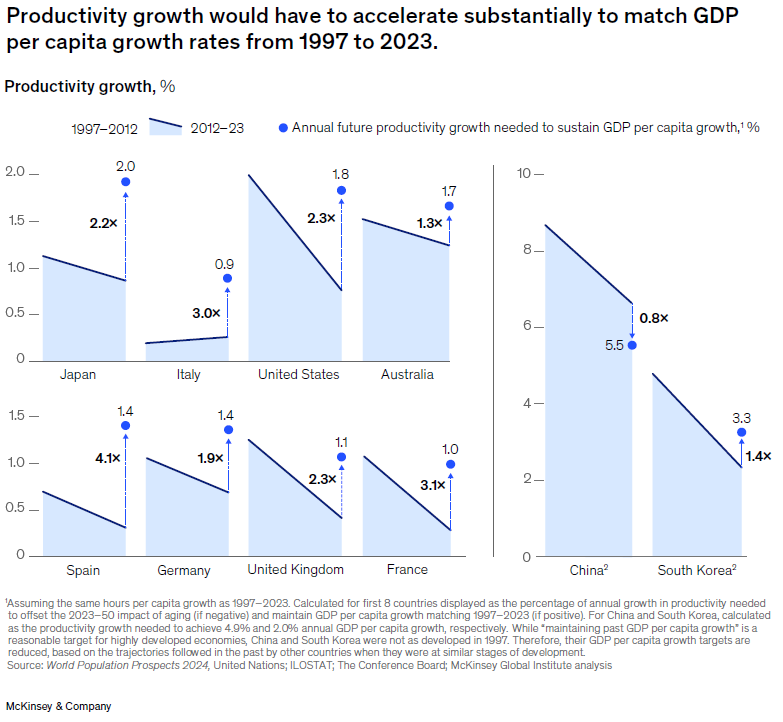

If people want to keep working the same hours, however, economies are going to have to make some really dramatic improvements in productivity (outside of China, where productivity growth has been far higher than anywhere in the west). Across the west, most countries would need to treble their annual rates of productivity growth to keep their economy growing at the same speed. That implies a big turnaround after years of steady declines, and it’s very hard to see it happening:

Some combination of the above is going to be needed. People will have to work longer hours and retire later, which will mean reversing generations of gains made by workers. Improvements in longevity and health care would help this to happen, but the passionate objections to attempts to raise retirement ages (most dramatically in France, but nobody wants to have to wait longer for their pension) show how difficult this will be. That leaves, it seems to me, two obvious conclusions:

- Productivity has to improve somehow. That’s easier said than done, as the history of the last few decades makes clear, but the fact that it’s growing so urgent to find a way to get each worker producing more does suggest that the excitement over artificial intelligence has some justification. AI really might liberate a lot of people from jobs altogether, and boost others’ productivity. It does make sense to invest a lot in a technology that has true potential to solve the productivity problem.

- Heavy emigration from sub-Saharan Africa makes immense sense. The region will be producing more workers, who can fill the gaps emerging in the labor forces everywhere else. The region has made great progress in eliminating extreme poverty, but is much less far forward in the attempt to build a prosperous middle class. Immigrant remittances, and the job experience to be gained overseas, would be just what the region is needing. Solving the problems caused by falling fertility in the developed world while bringing some prosperity to the region where it is most conspicuously lacking would make eminent sense.

Of course, western populations do not at the moment seem ready to encourage an influx of African migrant labor. Quite the reverse. But the problem can only intensify, and that will force us all into examining some unpalatable alternatives.